A local history

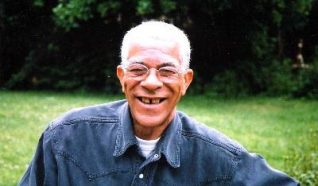

Bert Williams is a very enthusiastic and knowledgeable man. He is also very busy. He is the creator of the Black History website; he produces and distributes leaflets on Black history and on local Black community events; he organises exhibitions held at the Old Market, the University, in schools and prisons. When not doing any of those things he continues with his research, which involves the painstaking reading of old books and documents. He talked to me about the Black History of Brighton and Hove and told me some very interesting stories relating to the History Trail.

Starts in neolithic times

Black history focuses on the history of Asian, African and African Caribbean peoples. It documents the largely unknown but valuable economic and cultural contribution of Black people to history. In Brighton and Hove the story starts as early as Neolithic times when a dark skinned tribe lived in Sussex. The remains of Roman forts shows that many Roman soldiers, drawn from countries all over the Roman Empire, including Africa and Arabia, were garrisoned in here.

Beginning of the slave trade

However, the continuous history of Black people in the town dates from the mid 16th century and the beginning of the slave trade. Many Black people worked as slave-servants, musicians, footman, soldiers and sailors in Brighton. The 10th Hussars, the Regent’s favourite regiment, were stationed in Brighton during the Regency period and included a number of Black soldiers.

A cricketer and an Emperor

Many Black people were also very well known. In 1895 Ranji, an Indian, started to play cricket for Sussex and became the first batsman ever to score over 3,000 runs in a season. He went on to become the first Indian to play test cricket and became the second batsman after W.G.Grace.

Haile Selassie, Emperor of Abyssinia, travelled to Brighton during his exile in Britain. One photo appearing in the Brighton and Hove Herald showed him and his family with the Mayor of Brighton.

The first English wedding

Sarah Forbes Bonetta was an African princess who was orphaned at an early age in her home country. She was captured and given as a gift to Queen Victoria, who was so impressed with the girl that she allowed her to get married. So it was that the first royal African wedding in England was held at St Nicholas Church in 1862. Ten carriages arrived at the church and the guests included “white ladies with African gentlemen, and African ladies with white gentlemen until all the space was filled. The bridesmaids were 16 in number.” (Source: Brighton Gazette, August 1862)

A child prodigy

In the 18th Century an African prince married a white European woman and they had two sons who were both talented musicians. George Bridgetower, the elder son born in 1778, was an infant prodigy. He played for George III when he was only nine years old and performed at the Royal Pavilion for fourteen years. He is best remembered today for his friendship with Beethoven. The composer praised the musician as “a very capable virtuoso who has complete command of his instrument”. Beethoven wrote a new piece – the Kreutzer Sonata – for the Afro-European violinist and an autographed copy bears the inscription “Sonata mulattica composta per il mullato”.

A hospital for Indian soldiers

The Pavilion was also famous for being a hospital for Indian soldiers during World War I. Very early on in World War I it was apparent that the Allies did not have enough forces to cover all the areas of fighting – for example in North Africa, Europe and the Middle East. So it was decided to employ troops from the Indian Army. Soldiers wounded in battle on the Western front needed to be hospitalized, so King George V had requested the use of the Royal Pavilion as a militarily hospital for wounded Indian soldiers.

The Royal Pavilion estate had to be able to accommodate the three main Indian religions: Hindu, Muslim and Sikh, in order for soldiers to be able to worship. The Sikh temple was a marquee erected in the Pavilion grounds. The Muslims were able to use the lawn in front of the Dome, as this was facing East. Nine kitchens were erected in the grounds to cater for the various religions.

The Royal Pavilion was not the only building in Brighton to be transformed into a militarily hospital for wounded Indian soldiers, the Brighton General Hospital renamed the Kitchener General Indian Hospital, and the York Place School, were all converted and especially adapted for the wounded Indian soldiers.

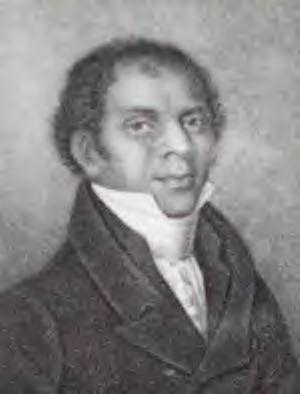

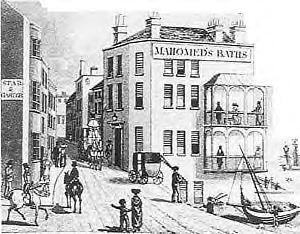

Dean Mahomed and his Baths

Just off the sea front in Kings Road stands the Queen’s Hotel. On this site used to stand Mahomed’s Baths. Sake Dean Mahomed was born in 1759 and grew up in India. He served in the English East India Company Bengal Army as a trainee surgeon. In 1786, at age 25, he immigrated to Ireland where he wrote and published his book entitled ‘The Travels of Dean Mahomet’. He became the first Indian to write a book in English.

Mahomed moved to London, where he opened the first Indian take away restaurant in England – the Hindustani Coffee House. Then, in 1814 he and Jane, his Irish wife, moved to Brighton and opened the first masseur vapour bath in England. He described the treatment in a local paper as ‘The Indian Medicated Vapour Bath……a cure to many diseases and giving full relief when every thing fails; particularly rheumatic and paralytic, gout, stiff joints, old sprains, lame legs, aches and pains in the joints’.

So successful was his treatment that hospitals referred patients to him. Both King George IV and William IV appointed him as their “shampooing surgeon” in Brighton.

Frederick Ackbar Mahomed, Dean Mahomed’s grandson, went on to study medicine at the Royal Sussex County Hospital. In October 1869, the young Akbar, aged 20, left the hospital and went to Guys Hospital in London. In 1870 and 1871 Akbar won universal praise for his work at Guys. Two years running he won the Physical Society Prize for developing the sphygmograph (for measuring the pressure of the pulse).

His first unpublished paper was presented to the Pupils Physical Society at Guys Hospital, detailing his findings from 1872 to 1873, describing his modification and use of the sphygmograph. Akbar qualified as a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1872, and in 1874 gained membership to the Royal College of Physicians.

The Black History Website with further material and pictures can be found at www.black-history.org.uk

Comments about this page

There is no evidence that a people of Sub Saharan African (ie Black) origin lived anywhere in Britain in neolithic times.

With regards to Roman soldiers, most of those stationed in Britain that were non-European were from Syria, Asia Minor and Mesopotamia, and were not black African. Aramaic graffiti can be found on Hadrian’s Wall. It should also be noted that the term Africa, in Roman times referred to an area of northern Algeria and Tunisia only, the inhabitants of this area were Semitic peoples, not Black Africans. A lot of the other people mentioned in the article are in fact Asians, and by definition are not Black. Hormuz Rassam, the Archaeologist who helped unearth the Epic of Gilgamesh lived in Brighton also. He was an ethnic Assyrian from what is now Iraq, like myself. Neither he nor I are black.

Northern Algerians and Tunisians were Black Africans in Roman times, in fact Romans were not caucasion throughout history and were in fact mulatto. Stop trying to white wash history. Black people travelled around the globe along time before Europeans even knew what boats were.

Paul Daniel, 2009: “There is no evidence that a people of Sub Saharan African (ie Black) origin lived anywhere in Britain in neolithic times.” And indeed, when such an assertion is ever made, you can be the first to complain about it. Of course, it was not. The actual statement was “Black history focuses on the history of Asian, African and African Caribbean peoples. It documents the largely unknown but valuable economic and cultural contribution of Black people to history. In Brighton and Hove the story starts as early as Neolithic times when a dark skinned tribe lived in Sussex.” There is nothing difficult about reading these self-explanatory sentences. Of course, I am writing 10 years after your comment with the benefit of having actually researched the point that made your blood boil first, rather than jumping to trenchant denial of a strawman fallacy.

As it stands, the statement is a perfectly valid summary of what is currently known of prehistoric populations. In fact, more strongly of the earlier Mesolithic. An analysis of the nuclear DNA of ‘Cheddar Man’ in 2018 confirmed his relationship to the Mesolithic Western European Hunter-Gatherers (WHG) population, and genetic markers indicating high probability of green/hazel eyes, lactose intolerance, dark curly or wavy hair, and dark to very dark skin.

‘Whitehawk Woman’, our earliest known ‘Brightonian’, represents a member of a new population that appears in the British Isles from around 6,000 years ago. No DNA has been able to be extracted from her remains, but extrapolation has been made based upon analysed remains of similar age found near Stonehenge and other sites in Britain: to suggest she was likely a member of a migration – originating in Anatolia, possibly around the Aegean coast, travelling via Iberia to the British Isles – living in Sussex around 3,600 BCE, which brought the technologies of animal husbandry and farming into the region for the first time – regularly suggested as the most significant change in human history. The genetic evidence from those remains suggests the hair, eye and skin pigmentation used in a recent reconstruction made by the Natural History Museum and on display in the Elaine Evans Archaeology Gallery at Brighton Museum and Art Gallery.

Subsequent migrations associated with the Beaker cultures and the Celtic peoples would ultimately supersede 90% of the genetic heritage of Whitehawk Woman’s population in modern ancestry, as hers had replaced almost all of the genetic heritage of the WHGs. Yet, she lived and is part of our local story, and still perhaps a small part of who many of us are.

Add a comment about this page