Brighton: Location and functions

Please note that this text is an extract from a reference work written in 1990. As a result, some of the content may not reflect recent research, changes and events.

Brighton is an important residential, commercial, educational, entertainment, tourist and conference centre on the Sussex coast, forty-six miles due south of London and just east of the head of a wide bay formed by Selsey Bill and Beachy Head, at 50.49 N latitude, 00.08 W longitude.

The settlement, which was well established by the time of the Domesday Book in 1086, grew up at the point where the Downs meet the sea to provide easy hill or valley routes to Lewes and beyond, and was probably originally situated on an extensive foreshore protected from the force of the Channel by an offshore submarine bar of shale; there may have also have been a small inlet, while flat ground behind the beach provided a convenient shelter for boats in time of storm. In medieval times the village grew with the success of the fisheries into a small town, but it fell into an economic depression in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

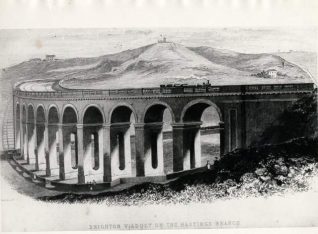

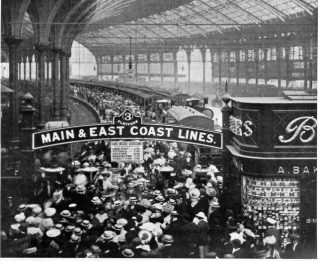

Around 1750 though, the wind of fortune turned again as the health resort function became established, chiefly at the prerogative of Dr Richard Russell (q.v.) of Lewes. As first the county and then London society flocked to the town, so the facilities for their amusement were developed, the libraries, theatre and assembly rooms which were modelled on those provided by the older inland spa towns. The town grew once more, the first authentic seaside resort in the country, and was eventually transformed into the largest and most fashionable resort of the era, the haunt of royalty and nobility, the rich and the famous. The population doubled in the ten years from 1811 to 1821, and the coming of the railway in the 1840 brought further rapid urban and industrial development; the first hoards of summer day-trippers from London also arrived, a new phenomenon that led to the development of a separate fashionable season in the winter. Suburban development on the slopes of the Downs followed from the 1870s until the 1960s to complete the town as we know it today.

Now, in the last years of the twentieth century, the resort function has diminished somewhat as the masses turn to Europe for guaranteed sunshine holidays, and more emphasis has been placed on short-stay holidays and also on the conference and exhibition trade which was worth £53 million to the town’s economy in 1988. The opening of the Brighton Centre in 1977 has stimulated a widespread hotel improvement programme, culminating in the new Ramada Renaissance (now the Hospitality Inn) in 1987, and further facilities will be provided in West Street and at the completed Marina project. The number of day-trippers has declined from up to ten million in the pre- and post-war eras to some two million per year, with another 670,000 staying for longer periods. The tourist, hotel and catering trade is still vital to the town and provides employment for around 8,000 people.

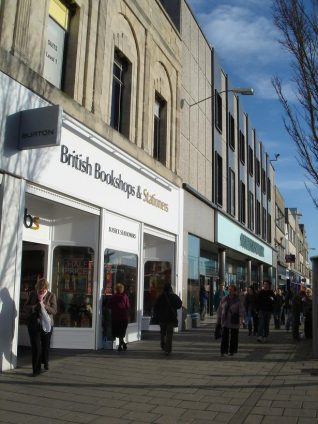

As a shopping centre, Brighton, with some 2,000 shops, has a variety matched only by the largest cities; nearly half these shops are located in the main centre around Western Road and the outdated Churchill Square, but the specialist shops of the Old Town and North Laine areas provide a great attraction for many, while the district centres of London Road, St James’s Street and Lewes Road fulfil the everyday needs of residents. The construction of large ‘superstores’ at Lewes Road, Nevill Road, Hollingbury and the Marina in 1985-7, and the provision of retail warehouses may well produce marked changes in the nature of town centre shopping, however.

Some 65,000 people are employed in the town, chiefly in the service, administrative and distributive sectors. Around 25,000 commute daily into Brighton while 15,000 travel out each day. Heavy industry virtually disappeared with the closure of the railway works in the 1950s, while light engineering, chiefly on the industrial estates, has declined since the 1970s although many new small businesses have opened since 1980. Widespread office construction means that a large proportion of employees now work in financial, administrative and corporate areas.

In the education sector, Brighton, with a university, polytechnic and college of technology, provides tuition for 10,000 or so full-time higher education students. There are also around thirty summer language schools with an annual turnover of some 25,000 foreign students. Indeed, education is so important that it is now the largest single employment sector.

Entertainment is provided by the usual seaside facilities plus a multitude of concert halls, night-clubs, public houses, theatres and cinemas, while the range of restaurants is said to be second only to that of London itself. The Brighton Festival, first staged in 1967, is now the second largest arts festival in the country after Edinburgh’s. Spectator sport facilities are provided throughout the twin towns, but public sporting and recreational facilities are woefully lacking and a number of new sports centres are required as leisure time increases; facilities to be provided at the Marina and Moulsecoomb will improve the situation.

Now that the widespread destruction of the Regency and Victorian heritage has ceased, the bane of Brighton’s life must surely be the traffic congestion experienced every day in the town centre. The combination of narrow and hilly streets and the sheer volume of traffic generated by commercial activity makes public transport unreliable and brings the town almost to a standstill. The long-promised bypass is unlikely to ease the congestion in the heart of the town, and only radical policies such as the prohibition of town-centre through traffic envisaged in the ‘Breeze into Brighton’ plan of September 1988 will improve the situation.

Finally, the population of Brighton is surely as diverse as that of anywhere in the country. The centre of a conurbation of some 280,000 people from Saltdean to Shoreham, the town has extensive council estates and thousands living on poverty levels, and yet it is one of the most expensive in the country and extremely attractive to the ‘professional classes’. The south coast is renowned for its retired population, but at the same time Brighton has some 10,000 students and numerous other young people in its many bed-sitters. The gay community is second in size only to London’s. The diversity of the population contributes greatly to cultural life and adds to the rather attractive eccentricities of the town. Politically, Brighton has provided the only Sussex Labour M.P., and is probably unique for so large a resort in having a Labour-controlled council.

Today’s Brighton is therefore primarily a service town, a function it has performed for the last two-hundred years or more, and is rightfully the capital of Sussex in all but name. It remains distinct from other British seaside resorts and towns because of its unique fashionable past and splendid architecture, its liberal and cosmopolitan culture, and the enduring contrast between the town’s two faces: the rich and fashionable; and the poor and shabby.

Any numerical cross-references in the text above refer to resources in the Sources and Bibliography section of the Encyclopaedia of Brighton by Tim Carder.

The following resource(s) is quoted as a general source for the information above: {2,11,277}

No Comments

Add a comment about this page